Social realism

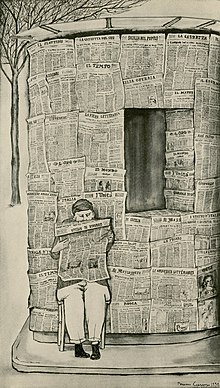

Social realism is the term used for work produced by painters, printmakers, photographers, writers and filmmakers that aims to draw attention to the real socio-political conditions of the working class as a means to critique the power structures behind these conditions. While the movement's characteristics vary from nation to nation, it almost always uses a form of descriptive or critical realism.[1]

The term is sometimes more narrowly used for an art movement that flourished in the interwar period as a reaction to the hardships and problems suffered by common people after the Great Crash. In order to make their art more accessible to a wider audience, artists turned to realist portrayals of anonymous workers as well as celebrities as heroic symbols of strength in the face of adversity. The goal of the artists in doing so was political as they wished to expose the deteriorating conditions of the poor and working classes and hold the existing governmental and social systems accountable.[2]

Social realism should not be confused with socialist realism, the official Soviet art form that was institutionalized by Joseph Stalin in 1934 and was later adopted by allied Communist parties worldwide. It is also different from realism as it not only presents conditions of the poor, but does so by conveying the tensions between two opposing forces, such as between farmers and their feudal lord.[1] However, sometimes the terms social realism and socialist realism are used interchangeably.[3]

Origins

[edit]

Social realism, as an art movement that became prominent in the US between the two world wars, as a reaction to the increasing hardship for ordinary people, was influenced by the social realist tradition in France which had existed for decades.[4]

Social realism traces back to 19th-century European Realism, including the art of Honoré Daumier, Gustave Courbet and Jean-François Millet. Britain's Industrial Revolution aroused concern for the poor, and in the 1870s the work of artists such as Luke Fildes, Hubert von Herkomer, Frank Holl, and William Small were widely reproduced in The Graphic.

In Russia, Peredvizhniki or "Social Realism" was critical of the social environment that caused the conditions pictured, and denounced the Tsarist period. Ilya Repin said that his art work aimed "to criticize all the monstrosities of our vile society" of the Tsarist period. Similar concerns were addressed in 20th-century Britain by the Artists' International Association, Mass Observation and the Kitchen sink school.[1]

Social realist photography draws from the documentary traditions of the late 19th century, such as the work of Jacob A. Riis, and Maksim Dmitriyev.[1]

Ashcan school

[edit]

In about 1900, a group of Realist artists led by Robert Henri challenged the American Impressionism and academics, in what would become known as the Ashcan school. The term was suggested by a drawing by George Bellows, captioned Disappointments of the Ash Can, which appeared in the Philadelphia Record in April 1915.[5]

In paintings, illustrations, etchings, and lithographs, Ashcan artists concentrated on portraying New York's vitality, with a keen eye on current events and the era's social and political rhetoric. H. Barbara Weinberg of The Metropolitan Museum of Art has described the artists as documenting "an unsettling, transitional time that was marked by confidence and doubt, excitement and trepidation. Ignoring or registering only gently harsh new realities such as the problems of immigration and urban poverty, they shone a positive light on their era."[5]

Notable Ashcan works include George Luks' Breaker Boy and John Sloan's Sixth Avenue Elevated at Third Street. The Ashcan school influenced the art of the Depression era, including Thomas Hart Benton's mural City Activity with Subway.[1]

Art movement

[edit]

The term dates on a broader scale to the Realist movement in French art during the mid-19th century. Social realism in the 20th century refers to the works of the French artist Gustave Courbet and in particular to the implications of his 19th-century paintings A Burial At Ornans and The Stone Breakers, which scandalized French Salon–goers of 1850,[6] and is seen as an international phenomenon also traced back to European realism and the works of Honoré Daumier and Jean-François Millet.[1] The social realist style fell out of fashion in the 1960s but is still influential in thinking and the art of today.

In the more limited meaning of the term, Social Realism with roots in European Realism became an important art movement during the Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s. As an American artistic movement it is closely related to American scene painting and to Regionalism. American Social Realism includes the works of such artists as those from the Ashcan School including Edward Hopper, and Thomas Hart Benton, Will Barnet, Ben Shahn, Jacob Lawrence, Paul Meltsner, Romare Bearden, Rafael Soyer, Isaac Soyer, Moses Soyer, Reginald Marsh, John Steuart Curry, Arnold Blanch, Aaron Douglas, Grant Wood, Horace Pippin, Walt Kuhn, Isabel Bishop, Paul Cadmus, Doris Lee, Philip Evergood, Mitchell Siporin, Robert Gwathmey, Adolf Dehn, Harry Sternberg, Gregorio Prestopino, Louis Lozowick, William Gropper, Philip Guston, Jack Levine, Ralph Ward Stackpole, John Augustus Walker and others. It also extends to the art of photography as exemplified by the works of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, Lewis Hine, Edward Steichen, Gordon Parks, Arthur Rothstein, Marion Post Wolcott, Doris Ulmann, Berenice Abbott, Aaron Siskind, and Russell Lee among several others.[citation needed]

In Mexico, the painter Frida Kahlo is associated with the social realism movement. Also in Mexico was the Mexican muralist movement that took place primarily in the 1920s and 1930s; and was an inspiration to many artists north of the border and an important component of the social realism movement. The Mexican muralist movement is characterized by its political undertones, the majority of which are of a Marxist nature, and the social and political situation of post-revolutionary Mexico. Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Rufino Tamayo are the best known proponents of the movement. Santiago Martínez Delgado, Jorge González Camarena, Roberto Montenegro, Federico Cantú Garza, and Jean Charlot, as well as several other artists participated in the movement.

Many artists who subscribed to social realism were painters with socialist (but not necessarily Marxist) political views. The movement therefore has some commonalities with the socialist realism used in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, but the two are not identical – social realism is not an official art, and allows space for subjectivity. In certain contexts, socialist realism has been described as a specific branch of social realism.

Social realism has been summarized as follows:

Social Realism developed as a reaction against idealism and the exaggerated ego encouraged by Romanticism. Consequences of the Industrial Revolution became apparent; urban centers grew, slums proliferated on a new scale contrasting with the display of wealth of the upper classes. With a new sense of social consciousness, the Social Realists pledged to "fight the beautiful art", any style which appealed to the eye or emotions. They focused on the ugly realities of contemporary life and sympathized with working-class people, particularly the poor. They recorded what they saw ("as it existed") in a dispassionate manner. The public was outraged by Social Realism, in part, because they didn't know how to look at it or what to do with it.[7]

In the United States

[edit]

Social realism in the United States was inspired by the muralists active in Mexico after the Mexican Revolution of 1910.

Farm Security Administration project

[edit]Social realist photography reached a culmination in the work of Dorothea Lange, Walker Evans, Ben Shahn, and others for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) project, from 1935 to 1943.[1]

After World War I, the booming U.S. farm economy collapsed from overproduction, falling prices, unfavorable weather, and increased mechanization. Many farm laborers were out of work and many small farming operations were forced into debt. Debt-ridden farms were foreclosed by the thousands, and sharecroppers and tenant farmers were turned from the land. When Franklin D. Roosevelt entered office in 1932, almost two million farm families lived in poverty, and millions of acres of farm land had been ruined from soil erosion and poor farming practices.[8]

The FSA was a New Deal agency designed to combat rural poverty during this period. The agency hired photographers to provide visual evidence that there was a need, and that FSA programs were meeting that need. Ultimately this mission accounted for over 80,000 black and white images, and is now considered one of the most famous documentary photography projects ever.[9]

WPA and Treasury art projects

[edit]The Public Works of Art Project was a program to employ artists during the Great Depression. It was the first such program, running from December 1933 to June 1934. It was headed by Edward Bruce, under the United States Treasury Department and funded by the Civil Works Administration.[10]

Created in 1935, the Works Progress Administration was the largest and most ambitious New Deal agency, employing millions of unemployed people (mostly unskilled men) to carry out public works projects,[11] including the construction of public buildings and roads. In much smaller but more famous projects the WPA employed musicians, artists, writers, actors and directors in large arts, drama, media, and literacy projects.[11] Many of the artists employed under the WPA are associated with social realism. Social realism became an important art movement during the Great Depression in the United States in the 1930s. As an American artistic movement encouraged by New Deal art, social realism is closely related to American scene painting and to Regionalism.[12]

In Mexico, the painter Frida Kahlo is associated with the social realism movement. The Mexican muralist movement that took place primarily in the 1920s and 1930s was an inspiration to many artists north of the border and an important component of the social realism movement. The Mexican muralist movement is characterized by its political undertones, the majority of which are of a Marxist nature, and the social and political situation of post-revolutionary Mexico. Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco, and Rufino Tamayo are the best known proponents of the movement. Santiago Martínez Delgado, Jorge González Camarena, Roberto Montenegro, Federico Cantú Garza, and Jean Charlot, as well as several other artists participated in the movement.[13]

Many artists who subscribed to social realism were painters with socialist (but not necessarily Marxist) political views. The movement therefore has some commonalities with the Socialist Realism used in the Soviet Union and the Eastern Bloc, but the two are not identical – Social Realism is not an official art, and allows space for subjectivity. In certain contexts, socialist realism has been described as a specific branch of social realism.[13]

World-War II to present

[edit]With the onset of abstract expressionism in the 1940s, social realism had gone out of fashion.[14] Several WPA artists found work with the United States Office of War Information during WWII, making posters and other visual materials for the war effort.[15] After the war, although lacking attention in the art market, many social realist artists continued their careers into the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s and into the 2000s; throughout which, artists such as Jacob Lawrence, Ben Shahn, Bernarda Bryson Shahn, Raphael Soyer, Robert Gwathmey, Antonio Frasconi, Philip Evergood, Sidney Goodman, and Aaron Berkman continued to work with social realist modalities and themes.[16]

Whether in and out of fashion, social realism and socially conscious art-making continues today within the contemporary art world, including artists Sue Coe, Mike Alewitz, Kara Walker, Celeste Dupuy Spencer, Allan Sekula, Fred Lonidier, and others.[16]

Gallery

[edit]-

Thomas Hart Benton, People of Chilmark, 1920, Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Washington, D.C.

-

Walker Evans, Floyd Burroughs, Alabama cotton Sharecropper, Hale County, Alabama, c. 1935–1936, photograph

-

Ben Shahn, detail of The Passion of Sacco and Vanzetti (1967, mosaic), Syracuse University, Syracuse, NY

-

Walker Evans, Allie Mae Burroughs, Wife of a Cotton Sharecropper, Hale County, Alabama, c. 1935–1936, photograph

-

Arthur Rothstein, A Farmer and His Two Sons During a Dust Storm, Cimarron County, Oklahoma, 1936, photograph considered as an icon of the Dust Bowl

-

Santiago Martinez Delgado, mural for the 1933 Chicago International Fair

-

José Orozco, detail of mural Omnisciencia, 1925

-

Diego Rivera, recreation of Man at the Crossroads (renamed Man, Controller of the Universe), originally created in 1934

-

Constantin Meunier, Miner at the Exit of the Shaft, 1880s, Meunier Museum, Brussels

-

Eugène Laermans, Emigrants, central panel, 1896, Royal Museum of Fine Arts Antwerp

In Latin America

[edit]Muralists active in Mexico after the Mexican Revolution of 1910 created largely propagandizing murals which emphasized a revolutionary spirit and a pride in the traditions of the indigenous peoples of Mexico, and included Diego Rivera's History of Mexico from the Conquest to the Future, José Clemente Orozco's Catharsis, and David Alfaro Siqueiros's The Strike. These murals also encouraged social realism in other Latin American countries, from Ecuador (Oswaldo Guayasamín's The Strike) to Brazil (Cândido Portinari's Coffee).[1]

In Europe

[edit]

In Belgium, early representatives of social realism are found in the work of 19th century artists such as Constantin Meunier and Charles de Groux.[17][18] In Britain, artists such as the American James Abbott McNeill Whistler, as well as English artists Hubert von Herkomer and Luke Fildes had great success with realist paintings dealing with social issues and depictions of the "real" world. Artists in Western Europe also embraced social realism in the early 20th century, including Italian painter and illustrator Bruno Caruso, German artists Käthe Kollwitz, George Grosz, Otto Dix, and Max Beckmann; Swedish artist Torsten Billman; Dutch artists Charley Toorop and Pyke Koch; French artists Maurice de Vlaminck, Roger de La Fresnaye, Jean Fautrier, and Francis Gruber and Belgian artists Eugène Laermans and Constant Permeke.[1][19][20]

The political polarization of the period resulted in social realism's distinction from socialist realism becoming less obvious in public opinion, and by the mid-20th century abstract art had replaced it as the dominant movement in both Western Europe and the United States.[1]

France

[edit]Realism, a style of painting that depicts the actuality of what the eyes can see, was a very popular art form in France around the mid- to late-19th century. It came about with the introduction of photography – a new visual source that created a desire for people to produce things that look "objectively real". Realism was heavily against romanticism, a genre dominating French literature and artwork in the mid-19th century. Undistorted by personal bias, Realism believed in the ideology of external reality and revolted against exaggerated emotionalism. Truth and accuracy became the goals of many realists as Gustave Courbet.[21]

Russia and the Soviet Union

[edit]

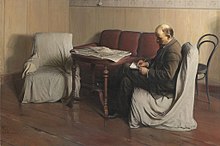

The French Realist movement had equivalents in all other Western countries, developing somewhat later. In particular, the Peredvizhniki or Wanderers group in Russia who formed in the 1860s and organized exhibitions from 1871 included many realists such as Ilya Repin and had a great influence on Russian art.

From that important trend came the development of socialist realism, which was to dominate Soviet culture and artistic expression for over 60 years. Socialist realism, representing socialist ideologies, was an art movement that represented social and political contemporary life in the 1930s, from a left-wing standpoint. It depicted subjects of social concern; the proletariat struggle – hardships of everyday life that the working class had to put up with, and heroically emphasized the values of the loyal communist workers.

The ideology behind social realism, communicated by depicting the heroism of the working class, was to promote and spark revolutionary actions and to spread the image of optimism and the importance of productiveness. Keeping people optimistic meant creating a sense of patriotism, which would prove very important in the struggle to produce a successful socialist nation. The Unions Newspaper, the Literaturnaya Gazeta, described social realism as "the representation of the proletarian revolution". During Joseph Stalin's reign, it was considered most important to use socialist realism as a form of propaganda in posters, as it kept people optimistic and encouraged greater productive effort, a necessity in his aim of developing Russia into an industrialized nation.

Vladimir Lenin believed that art should belong to the people and should stand on the side of the proletariat. "Art should be based on their feelings, thoughts, and demands, and should grow along with them",[22] said Lenin. He also believed that literature must be part of the proletariat's common cause.[22] After the revolution of 1917, leaders of the newly formed communist party were encouraging experimentation of different art types. Lenin believed that the style of art the USSR should endorse would have to be easy to understand (ruling out abstract art such as suprematism and constructivism) for the masses of illiterate people in Russia.[23][24][25]

A wide-ranging debate on art took place;[when?] the main disagreement was between those who believed in "Proletarian Art" which should have no connections with past art coming out of bourgeois society, and those (most vociferously Leon Trotsky) who believed that art in a society dominated by working-class values had to absorb all the lessons of bourgeois art before it could move forward at all.

The taking of power by Joseph Stalin's faction had its corollary in the establishment of an official art: on 23 April 1932, headed by Stalin, an organization formed by the central committee of the Communist Party developed the Union of Soviet Writers. This organization endorsed the newly designated ideology of social realism.

By 1934, all other independent art groups were abolished, making it nearly impossible for someone not involved in the Union of Soviet Writers to get work published. Any literary piece or painting that did not endorse the ideology of social realism was censored or banned. This new art movement, introduced under Joseph Stalin, was one of the most practical and durable artistic approaches of the 20th century. With the communist revolution came also a cultural revolution. It also gave Stalin and his Communist Party greater control over Soviet culture and restricted people from expressing alternative geopolitical ideologies that differed to those represented in socialist realism. The decline of social realism came with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.[citation needed]

In film

[edit]Social realism in cinema found its roots in Italian neorealism, especially the films of Roberto Rossellini, Vittorio De Sica, Luchino Visconti and to some extent Federico Fellini.[26][27]

In British cinema

[edit]Early British cinema used the common social interaction found in the literary works of Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy.[28] One of the first British films to emphasize realism's value as a social protest was James Williamson's A Reservist Before the War, and After the War in 1902. The film memorialized Boer War serviceman coming back home to unemployment. Repressive censorship during 1945–54 prevented British films from displaying more radical social positions.[28]

After World War I, the British middle-class generally responded to realism and restraint in cinema, while the working-class generally favored Hollywood genre movies. Thus realism carried connotations of education and high seriousness. These social and aesthetic distinctions would soon become running themes as social realism is now associated with the arthouse auteur, while mainstream Hollywood films are shown at the multiplex.[28]

Producer Michael Balcon revived this distinction in the 1940s, referring to the British industry's rivalry with Hollywood in terms of "realism and tinsel". Balcon, the head of Ealing Studios, became a key figure in the emergence of a national cinema characterized by stoicism and verisimilitude. Critic Richard Armstrong said: "Combining the objective temper and aesthetics of the documentary movement with the stars and resources of studio filmmaking, 1940s British cinema made a stirring appeal to a mass audience."[28]

Social realism in cinema was reflecting Britain's transforming wartime society. Women were working alongside men in the military and its munitions factories, challenging pre-assigned gender roles. Rationing, air raids and unprecedented state intervention in the life of the individual encouraged a more social philosophy and worldview. Social realist films of the era include Target for Tonight (1941), In Which We Serve (1942), Millions Like Us (1943), and This Happy Breed (1944). Historian Roger Manvell wrote, "As the cinemas [closed initially because of the fear of air raids] reopened, the public flooded in, searching for relief from hard work, companionship, release from tension, emotional indulgence and, where they could find them, some reaffirmation of the values of humanity."[28]

In the postwar period, films like Passport to Pimlico (1949), The Blue Lamp (1949), and The Titfield Thunderbolt (1952) reiterated gentle patrician values, creating a tension between the camaraderie of the war years and the burgeoning consumer society.[28]

Sydney Box's arrival as head of Gainsborough pictures in 1946 saw a transition from the Gainsborough melodramas, which had been successful during the war years, to social realism. Issues such as short-term sexual relationships, adultery, and illegitimate births flourished during the Second World War[29] and Box, who favoured realism over what he termed as "flamboyance fantasy",[30] brought these and other social issues, such as child adoption, juvenile delinquency, and displaced persons to the fore with films such as When the Bough Breaks (1947), Good-Time Girl (1948), Portrait from Life (1948), The Lost People (1949), and Boys in Brown (1949). Films of new rapidly expanding forms of leisure by working class families in postwar Britain were also represented by Box in Holiday Camp (1947), Easy Money (1948), and A Boy, a Girl and a Bike (1949).[31] Box remained determined on making social realism films, even after Gainsborough closed in 1951, when he said in 1952 "No film has yet been made of the Tolpuddle Martyrs, the Suffragette Movement, the National Health Service as it is today, or the scandals of the patent medicines, oil control in the World, or armaments manufactured for profit."[32] However, he would not go on to make these types of stories into films, instead focusing on issues related to abortion, teenage prostitution, bigamy, child neglect, shoplifting, and drug trafficking in films such as Street Corner (1953), Too Young to Love (1959), and Subway in the Sky (1959).[33]

A British New Wave movement emerged in the 1950s and 1960s. British auteurs like Karel Reisz, Tony Richardson, and John Schlesinger brought wide shots and plain speaking to stories of ordinary Britons negotiating postwar social structures. Relaxation of censorship enabled film makers to portray issues such as prostitution, abortion, homosexuality, and alienation. Characters included factory workers, office underlings, dissatisfied wives, pregnant girlfriends, runaways, the marginalized, the poor, and the depressed. The New Wave protagonist was usually a working-class male without bearings in a society in which traditional industries and the cultures that went with them were in decline.[28]

Mike Leigh and Ken Loach also make contemporary social realist films.[34]

List of British New Wave films

[edit]- Room at the Top (1958)

- Saturday Night and Sunday Morning (1960)

- The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962)

- A Kind of Loving (1962)

In Indian cinema

[edit]Social realism was also adopted by Hindi films of the 1940s and 1950s, including Chetan Anand's Neecha Nagar (1946), which won the Palme d'Or at the first Cannes Film Festival, and Bimal Roy's Two Acres of Land (1953), which won the International Prize at the 1954 Cannes Film Festival. The success of these films gave rise to the Indian New Wave, with early Bengali art films such as Ritwik Ghatak's Nagarik (1952) and Satyajit Ray's The Apu Trilogy (1955–59). Realism in Indian cinema dates back to the 1920s and 1930s, with early examples including V. Shantaram's films Indian Shylock (1925) and The Unaccpected (1937).[37]

List of neorealist/social realist films in American cinema

[edit]- Body and Soul (1947)

- Thieves' Highway (1949)

- The Young Lovers (1949)

- Outrage (1950)

- Hard, Fast and Beautiful (1951)

- The Bigamist (1953)

- The Hitch-Hiker (1953)

- Little Fugitive (1953)

- Salt of the Earth (1954)

- On the Bowery (1957)

- Shadows (1959)

- The Exiles (1961)

- The Cool World (1963)

- Nothing But a Man (1964)

- Wanda (1970)

- Dusty and Sweets McGee (1971)

- Killer of Sheep (1978)

- Northern Lights (1978)

- Bush Mama (1979)

- El Norte (1983)

- My Brother's Wedding (1983)

- Bless Their Little Hearts (1984)

- Stranger Than Paradise (1984)

- Down By Law (1986)

- Border Radio (1987)

- American Me (1992)

- Clerks (1994)

- Friday (1995)

- 8 Mile (2002)

- Half Nelson (2006)

- Chop Shop (2007)

- Frownland (2007)

- The Visitor (2007)

- Frozen River (2008)

- Sugar (2008)

- Wendy and Lucy (2008)

- Meek's Cutoff (2010)

- Winter's Bone (2010)

- Nebraska (2013)

- Tangerine (2015)

- American Honey (2016)

- Moonlight (2016)

- The Rider (2017)

- Patti Cake$ (2017)

- The Florida Project (2017)

- The Last Black Man in San Francisco (2018)

- Leave No Trace (2018)

- Roma (2018)

- Never Rarely Sometimes Always (2020)

- Red Rocket (2021)

Filmmakers associated with American neorealism/social realism

[edit]- Chloe Zhao

- Ramin Bahrani

- Sean Baker

- Charles Burnett

- Barry Jenkins

- John Cassavetes

- Shirley Clarke

- Ida Lupino

- Coleman Francis

- Jim Jarmusch

- Barbara Loden

- Kent Mackenzie

- Kelly Reichardt

Sources:[38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61]

List of artists

[edit]The following incomplete list of artists have been associated with social realism:

| Artist | Nationality | Field(s) | Years active |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abbot, Berenice | American | photography | 1923–1991 |

| Anand, Chetan | Indian | film | 1944–1997 |

| Barnet, Will | American | painting, illustration, printmaking | 1930–2012 |

| Bearden, Romare | American | painting | 1936–1988 |

| Beckmann, Max | German | painting, printmaking, sculpture | unknown–1950 |

| Bellows, George | American | painting, illustration | 1906–1925 |

| Benton, Thomas Hart | American | painting | 1907–1975 |

| Billman, Torsten | Swedish | printmaking, illustration, painting | 1930–1988 |

| Bishop, Isabel | American | painting, graphic design | 1918–1988 |

| Blanch, Arnold | American | painting, etching, illustration, printmaking | 1923–1968 |

| Bloch, Julius | American | painting | 1888–1966 |

| Bogen, Alexander | Polish/ Israeli | painting, etching, illustration, printmaking | 1916–2010 |

| Bourke-White, Margaret | American | photography | 1920s–1971 |

| Brocka, Lino | Filipino | Film | 1970–1991 |

| Cadmus, Paul | American | painting, illustration | 1934–1999 |

| Camarena, Jorge González | Mexican | painting, sculpture | 1929–1980 |

| Caruso, Bruno | Italian | painting, illustration, printmaking | 1943–2012 |

| Castejón, Joan | Spanish | painting, sculpture, illustration | 1945–present |

| Charlot, Jean | French | painting, illustration | 1921–1979 |

| Chua Mia Tee | Singaporean | painting | 1956–1976 |

| Counihan, Noel | Australian | painting, printmaking | 1930s–1986 |

| Curry, John Steuart | American | painting | 1921–1946 |

| Dehn, Adolf | American | lithography, painting, printmaking | 1920s–1968 |

| Delgado, Santiago Martínez | Colombian | painting, sculpture, illustration | 1925–1954 |

| de la Fresnaye, Roger | French | painting | 1912–1925 |

| de Vlaminck, Maurice | French | painting | 1893–1958 |

| Dix, Otto | German | painting, printmaking | 1910–1969 |

| Douglas, Aaron | American | painting | 1925–1979 |

| Evans, Walker | American | photography | 1928–1975 |

| Evergood, Philip | American | painting, sculpture, printmaking | 1926–1973 |

| Fautrier, Jean | French | painting, sculpture | 1922–1964 |

| Garza, Federico Cantú | Mexican | painting, engraving, sculpture | 1929–1989 |

| Ghatak, Ritwik | Indian | film, theatre | 1948–1976 |

| Gropper, William | American | lithography, painting, illustration | 1915–1977 |

| Grosz, George | German | painting, illustration | 1909–1959 |

| Gruber, Francis | French | painting | 1930–1948 |

| Guayasamín, Oswaldo | Ecuadorian | painting, sculpture | 1942–1999 |

| Guston, Philip | American | painting, printmaking | 1927–1980 |

| Gwathmey, Robert | American | painting | unknown–1988 |

| Henri, Robert | American | painting | 1883–1929 |

| Hine, Lewis | American | photography | 1904–1940 |

| Hirsch, Joseph | American | painting, illustration, printmaking | 1933–1981 |

| Hopper, Edward | American | painting, printmaking | 1895–1967 |

| Kahlo, Frida | Mexican | painting | 1925–1954 |

| Koch, Pyke | Dutch | painting | 1927–1991 |

| Kollwitz, Käthe | German | painting, sculpture, printmaking | 1890–1945 |

| Kuhn, Walt | American | painting, illustration | 1892–1939 |

| Lamangan, Joel | Filipino | Film, Television, Theater | 1991–present |

| Lange, Dorothea | American | photography | 1918–1965 |

| Lawrence, Jacob | American | painting | 1931–2000 |

| Lee, Doris | American | painting, printmaking | 1935–1983 |

| Lee, Russell | American | photography | 1936–1986 |

| Levine, Jack | American | painting, printmaking | 1932–2010 |

| Lozowick, Louis | American | painting, printmaking | 1926–1973 |

| Luks, George | American | painting, illustration | 1893–1933 |

| Marsh, Reginald | American | painting | 1922–1954 |

| Meltsner, Paul | American | painting | 1913–1966 |

| Montenegro, Roberto | Mexican | painting, illustration | 1906–1968 |

| Myers, Jerome | American | painting, drawing, etching, illustration | 1867–1940 |

| Orozco, José Clemente | Mexican | painting | 1922–1949 |

| O'Hara Mario | Filipino | Film | 1976–2012 |

| Parks, Gordon | American | photography, film | 1937–2006 |

| Pippin, Horace | American | painting | 1930–1946 |

| Portinari, Candido | Brazilian | painting | 1928–1962 |

| Prestopino, Gregorio | American | painting | 1930s–1984 |

| Ray, Satyajit | Indian | film | 1947–1992 |

| Reisz, Karel | British | film | 1955–1990 |

| Richardson, Tony | British | film | 1955–1991 |

| Rivera, Diego | Mexican | painting | 1922–1957 |

| Rothstein, Arthur | American | photography | 1934–1985 |

| Roy, Bimal | Indian | film | 1935–1966 |

| Schlesinger, John | British | film | 1956–1991 |

| Shahn, Ben | American | painting, illustration, graphic art, photography | 1932–1969 |

| Siporin, Mitchell | American | painting | unknown–1976 |

| Siqueiros, David Alfaro | Mexican | painting | 1932–1974 |

| Siskind, Aaron | American | photography | 1930s–1991 |

| Sloan, John French | American | painting | 1890–1951 |

| Soyer, Isaac | American | painting | 1930s–1981 |

| Soyer, Moses | American | painting | 1926–1974 |

| Soyer, Raphael | American | painting, illustration, printmaking | 1930–1987 |

| Stackpole, Ralph | American | sculpture, painting | 1910–1973 |

| Steichen, Edward | American | photography, painting | 1894–1973 |

| Sternberg, Harry | American | painting, printmaking | 1926–2001 |

| Tamayo, Rufino | Mexican | painting, illustration | 1917–1991 |

| Toorop, Charley | Dutch | painting, lithography | 1916–1955 |

| Ulmann, Doris | American | photography | 1918–1934 |

| Walker, John Augustus | American | painting | 1926–1967 |

| Williamson, James | British | film | 1901–1933 |

| Wilson, John Woodrow | American | lithography, sculpture | 1945–2001 |

| Wolcott, Marion Post | American | photography | 1930s–1944 |

| Wong, Martin | American | painting | 1946–1999 |

| Wood, Grant | American | painting | 1913–1942 |

| İlhan, Attilâ[62] | Turkish | poetry | 1942–2005 |

See also

[edit]- American realism

- British New Wave

- Gabriel Bracho, exponent of the social realism artistic movement in Venezuela

- Italian neorealism

- Kitchen sink realism

- Naturalism

- Realism

- Film

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Todd, James G.; Grove Art Online (2009). "Social Realism". Art Terms. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on 14 May 2015.

- ^ Social Realism defined at the MOMA

- ^ Max Rieser, The Aesthetic Theory of Social Realism, in: The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 16, No. 2 (December 1957), pp. 237-248

- ^ "SOCIALIST REALISM". Tate. Retrieved 3 January 2021.

- ^ a b Weinberg, H. Barbara. "The Ashcan School". Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ 1850; Dresden, destroyed 1945

- ^ "Social Realism". instruct.westvalley.edu. Retrieved 4 May 2008.

- ^ Gabbert, Jim. "Resettlement Administration". Encyclopedia of Oklahoma History and Culture. Oklahoma Historical Society. Archived from the original on 24 May 2013. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ Gorman, Juliet. "Farm Security Administration Photography". Jukin' It Out: Contested Visions of Florida in New Deal Narratives. Oberlin College & Conservatory. Retrieved 7 February 2013.

- ^ "History of the New Deal Art Projects". wpaMurals.com - New Deal Art During the Great Depression. Archived from the original on 30 October 2005. Retrieved 29 July 2005.

- ^ a b Eric Arnesen, ed. Encyclopedia of U.S. Labor and Working-Class History (2007) vol. 1 p. 1540

- ^ Regionalism: An American Art Movement - Artlove.co

- ^ a b "Social Realism, New Masses & Diego Rivera". the-artifice.com. 26 October 2020.

- ^ "Raphael Soyer | artnet". www.artnet.com. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ "Getting the Message Out". National Archives. 15 August 2016. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ a b "Social Realism - Concepts & Styles". The Art Story. Retrieved 12 February 2019.

- ^ Constantin Meunier at the Britannica

- ^ David Ethan Stark (1979). Charles de Groux and Social Realism in Belgian Painting, 1848-1875. Ohio State University.

- ^ Jeff Adams (2008). Documentary Graphic Novels and Social Realism. Peter Lang. pp. 34–. ISBN 978-3-03911-362-0.

- ^ James Fitzsimmons; Jim Fitzsimmons (1971). Art International. J. Fitzsimmons.

- ^ Nineteenth-Century French Realism|The Metropolitan Museum of Art|Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History

- ^ a b New Essentials of Unification Thought - Google Books (pg.337)

- ^ John Gordon Garrard, Carol Garrard, Inside the Soviet Writers' Union, I.B.Tauris, 1990, p. 23, ISBN 1850432600

- ^ Karl Ruhrberg, Klaus Honnef, Manfred Schneckenburger, Christiane Fricke, Art of the 20th Century, Part 1, Taschen, 2000, p. 161, ISBN 3822859079

- ^ Solomon Volkov, The Magical Chorus, Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2008, p. 68, ISBN 0307268772

- ^ Hallam, Julia, and Marshment, Margaret. Realism and Popular Cinema. Inside popular film. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2000.

- ^ World Cinema: The rise and fall of Italian Neo-realism - Flickering Myth

- ^ a b c d e f g Armstrong, Richard. "Social Realism". BFI Screen Online. Retrieved 4 February 2013.

- ^ Barrow, Sarah & White, John. (2008). Fifty Key British Films. Routledge. p.63. ISBN 9781283547352 Retrieved 27 April 2020 via Google Books

- ^ Harper, Sue. (2016). From Holiday Camp to High Camp: Women in British Feature Films. in Andrew Higson. (2016) Dissolving Views: Key Writings on British Cinema. Bloomsbury Academic p.105. ISBN 9781474290654 Retrieved 27 April 2020 via Google Books

- ^ Spicer, Andrew. (2006). Sydney Box. Manchester University Press. p.109. ISBN 9780719060007. Retrieved 27 April 2020 via Google Books

- ^ Harper, Sue. & Porter, Vincent. (2003). British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference. Oxford University Press p.159. ISBN 9780198159353 Retrieved 27 April 2020 via Google Books

- ^ Harper, Sue. & Porter, Vincent. (2003). British Cinema of the 1950s: The Decline of Deference. Oxford University Press pp.159-162. ISBN 9780198159353 Retrieved 27 April 2020 via Google Books

- ^ "British Realism". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ "FREE CINEMA (BRITISH SOCIAL REALISM) – Movie List". MUBI. Retrieved 12 July 2019.

- ^ "BFI Screenonline: Social Realism". www.screenonline.org.uk.

- ^ Banerjee, Santanu. "Neo Realism in Indian Cinema".

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ "The New Social Realism of American Cinema". Film School Rejects. 17 January 2018.

- ^ "American Neorealism, Part One: 1948-1984 | UCLA Film & Television Archive". www.cinema.ucla.edu.

- ^ "Jarmusch in Tucson". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ "Why Clerks Still Works". The Baffler. 6 December 2019.

- ^ Welch, Ara H. Merjian,Rhiannon Noel; Merjian, Ara H.; Welch, Rhiannon Noel (22 September 2020). "It's a Neorealist World".

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Jim Jarmusch. Stranger Than Paradise. 1984 | MoMA". The Museum of Modern Art.

- ^ Arabian, Alex (4 March 2020). "Exploring the New Age of Neorealism on Film". SlashFilm.com.

- ^ "The Neo Neo-Realist, PopMatters". 28 November 2005.

- ^ In the Peanut Gallery with Mystery Science Theater 3000 - Google Books (pgs. 62-63)

- ^ Salvato, Larry (26 February 2015). "15 Great American Movies Influenced by Italian Neo-Realism".

- ^ Salvato, Larry (26 February 2015). "15 Great American Movies Influenced by Italian Neo-Realism".

- ^ "UCR ARTS".

- ^ "Gregory Nava's film 'El Norte' marks 25th anniversary". Los Angeles Times. 28 January 2009.

- ^ "Critical Discussion Transforms Art: Haile Gerima, the L.A. Rebellion, and Cinema as Life, PopMatters". 18 November 2019.

- ^ Meyer, David N. (16 July 2008). "(Native) American Neo-Realism". The Brooklyn Rail.

- ^ "About "Neo-Neo Realism"". The New Yorker. 19 March 2009.

- ^ "How Sean Baker Became America's Neorealist". 6 January 2022 – via CineFix on YouTube.

- ^ Hudson, David. "American Neorealism". The Criterion Collection.

- ^ Northern Lights – The Public Cinema

- ^ American Neorealism Now|Current|The Criterion Collection

- ^ American Neorealism|Current|The Criterion Collection

- ^ The Trouble with Lupino - Comparative Cinema

- ^ "The Criterion Channel's March 2024 Lineup". The Criterion Channel. 14 February 2024.

- ^ Who Needs Social Realism? - Jewish Currents

- ^ Güngör, Bilgin (11 March 2019). "Atti̇lâ İlhan'in Özgün Toplumcu-Gerçekçi̇li̇k Anlayişi: "Sosyal Reali̇zm"". Motif Akademi Halkbilimi Dergisi (in Turkish). 12 (25): 188–202. doi:10.12981/mahder.509763. ISSN 1308-4445.

Media related to Social realism at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Social realism at Wikimedia Commons

- Social realism

- Art movements

- Social realist artists

- Modern art

- 1940s in American cinema

- 1950s in American cinema

- 1960s in American cinema

- 1970s in American cinema

- 1980s in American cinema

- 1990s in American cinema

- 2000s in American cinema

- 2010s in American cinema

- 2020s in American cinema

- Film styles

- 1940s in film

- 1950s in film

- 1960s in film

- Interwar period